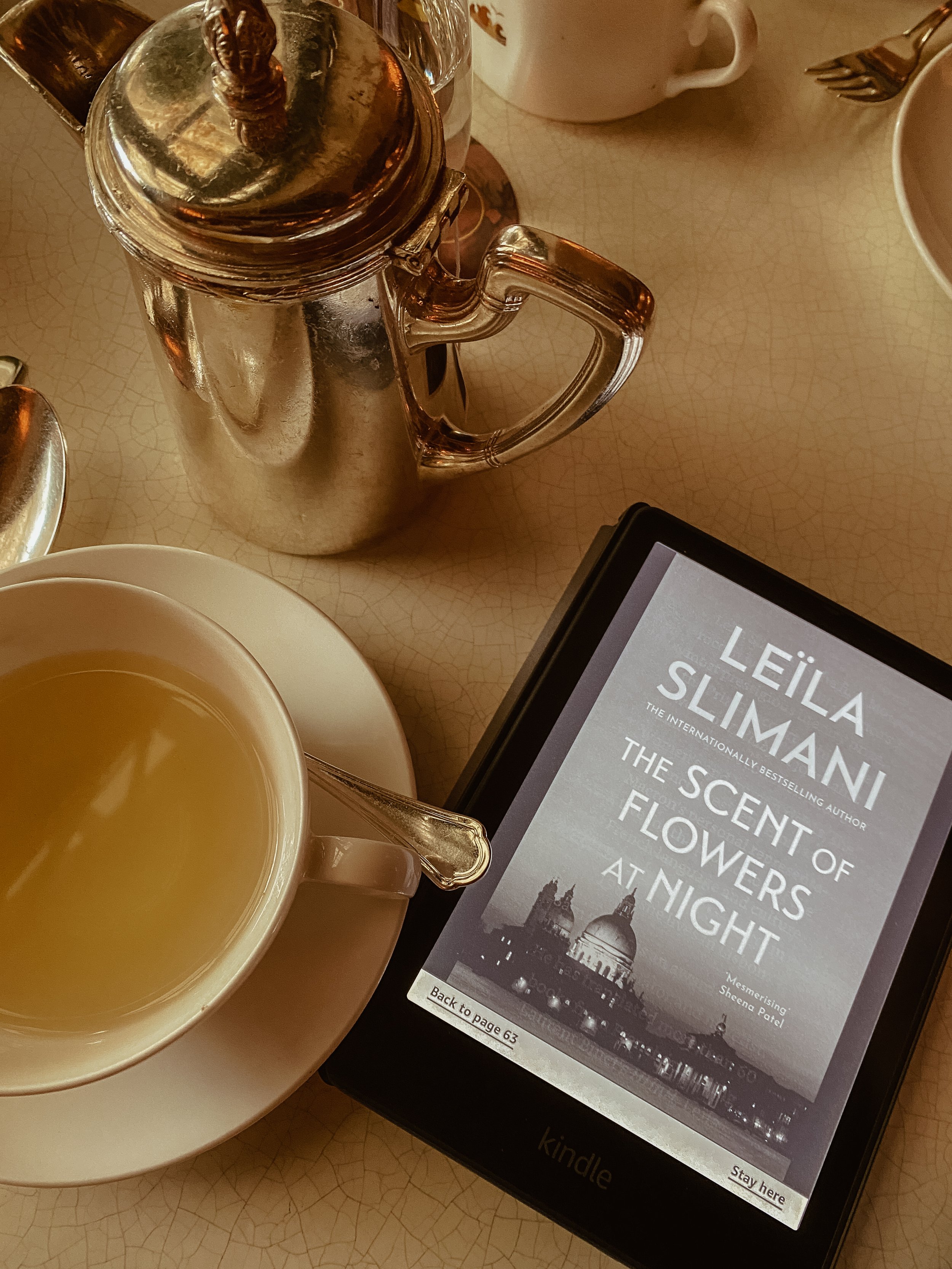

The Scent of Flowers at Night

The Scent of Flowers at Night, written by Leïla Slimani and translated by Sam Taylor, was recently recommended to me. Slimani, a prize-winning French-Moroccan novelist and journalist, also serves as the personal representative of French President Emmanuel Macron to the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. I was pleasantly surprised by the book’s simplicity, which nevertheless offers profound insights into the phenomenon of the Harraga and the ways in which social, cultural, and political contexts are seamlessly woven into literature.

The narrative is personal and intimate, imbued with a reflective tone as Slimani recounts her childhood in Rabat, Morocco, and her journey through life. This introspection unfolds during a one-night adventure in which Slimani agrees to be locked alone inside Venice’s Punta della Dogana Museum. Surrounded by art and enveloped in silence, she meditates on how writing becomes a quiet act of revealing one’s innermost thoughts, fears, and desires.

Leïla reminds us that, ultimately, each of us seeks a better life. Sometimes, that better life feels most attainable at night—a realm Slimani beautifully describes as:

“Night is the place where utopias have the scent of the possible, where we no longer feel constrained by petty reality. Night is the country of dreams where we discover that, in the secrecy of our heart, we are host to a multitude of voices and an infinity of worlds.”

The Scent of Flowers at Night is deeply humane, reminding readers of the unspoken, private corners of our inner selves—spaces that others cannot reach or tarnish. I was particularly struck by Slimani’s poignant observation:

“When you have several countries, several cultures, it can lead to a certain confusion. You are here and also from elsewhere. You always consider yourself a foreigner, but at the same time, you hate it when others see you that way. Our identity is both plural and partial.”

This sentiment resonates deeply, especially with immigrants and emigrants, who often grapple with the duality of belonging and estrangement. Slimani’s words are both a mirror and a comfort, offering a shared understanding of the complexity of identity and the universal longing for connection and home.